Narrative Voice — November 2025 Past Paper 1 —“I can’t say my own name”

Read the article here.

Elements of Narrative Voice

1. Who Is Speaking? (Perspective)

First person (“I”, “we”)

Second person (“you”)

Third person (he/she/they)

Multiple narrators

Unreliable narrator

2. How Do They Sound? (Tone)

Confessional

Reflective

Conversational

Formal

Critical

Humorous

Emotional

3. How Do They Involve the Reader?

Direct address

Rhetorical questions

Inclusive language (“we”, “us”)

4. How Do They Show Thoughts & Feelings?

Internal reflection

Anecdotes

Emotive language

Commentary/judgement

5. How Is the Voice Structured?

Shifts in register (personal → formal)

Dialogue / multiple voices

Repetition

Short/fragmented sentences

Circular framing

Essay

In the personal reflective feature article “‘I can’t say my own name’: The pain of language loss in families”, written for readers of the BBC, an international news platform, particularly adults from migrant or multilingual backgrounds, as well as educators and parents concerned with cultural identity, Mithu Sanyal humanises the issue of heritage language loss by intertwining personal testimony with sociolinguistic research. Through a carefully constructed narrative voice, shaped by perspective, tone, reader engagement, emotional reflection, and structural development, the article reframes language loss from an individual failing into a broader social phenomenon with emotional and relational consequences.

The article is written primarily in first-person narration, immediately establishing intimacy and authenticity. The opening line, “Do you want to know a secret?”, situates the reader within a direct and personal exchange. The repeated use of “I”, “I was talking to a friend”, “I can’t even say my own name”, “I start crying”, ensures that language loss is first encountered as a lived experience rather than an abstract concept. However, the perspective gradually widens. The line “Many of us, as it turns out” marks a deliberate shift from singular to collective identity. This movement from “I” to “us” reframes the experience as shared rather than exceptional. By structuring the narrative voice this way, Sanyal challenges the assumption that language loss reflects personal deficiency and instead positions it within a wider social pattern. The headline reinforces this perspective visually. The quotation “‘I can’t say my own name’” foregrounds first-person testimony, while the subtitle broadens the scope to “The pain of language loss in families.” Even before reading the article, the audience sees the movement from individual voice to collective issue.

The dominant tone at the beginning is confessional and vulnerable. Words such as “secret” and “shameful” create emotional exposure. The rhetorical question “What kind of child doesn’t learn their father’s language?” reveals internalised judgement and self-blame. As the article progresses, the tone shifts toward reflection and measured analysis. The introduction of research, including statistics showing that 12% to 44% of bilingually raised children end up speaking only one language, introduces a more formal register. Yet the tone never becomes detached; instead, the reflective quality persists, particularly in the admission “I’d thought there was something seriously wrong with me.” By the conclusion, the tone becomes gently evaluative: “It’s a matter of changing attitude.” This shift signals growth. The narrative voice moves from private shame to calm social commentary, reinforcing the purpose of reframing the issue.

Sanyal actively engages the reader through direct address, rhetorical questions, and inclusive language. The opening question invites immediate participation, while “What kind of child doesn’t learn their father’s language?” forces readers to confront assumptions that may mirror the narrator’s earlier self-judgement. The inclusive phrase “Many of us” reduces isolation and aligns the reader with the writer. Rather than positioning herself as uniquely deficient, Sanyal invites readers to see language loss as a shared experience shaped by social forces. This involvement subtly shifts responsibility away from the individual and toward broader societal attitudes.

The article relies heavily on thoughts and feelings conveyed through internal reflection, anecdote, and emotive language to humanise the issue. The anecdote about Jacinta Nandi functions as a relatable entry point, grounding the discussion in lived experience before introducing research. Emotive vocabulary, “shameful”, “seriously wrong”, “worthless”, conveys the psychological impact of language loss. The repetition in “Worthless. Worthless!” intensifies this emotional dimension, illustrating how children may internalise societal messages about the value of their heritage language. Short, isolated sentences such as “Yes, that’s right, I can’t even say my own name” visually and emotionally emphasise vulnerability. The moment “At this point in the interview I start crying” marks the emotional climax of the piece. By explicitly revealing tears, Sanyal underscores the enduring emotional consequences of linguistic disconnection.

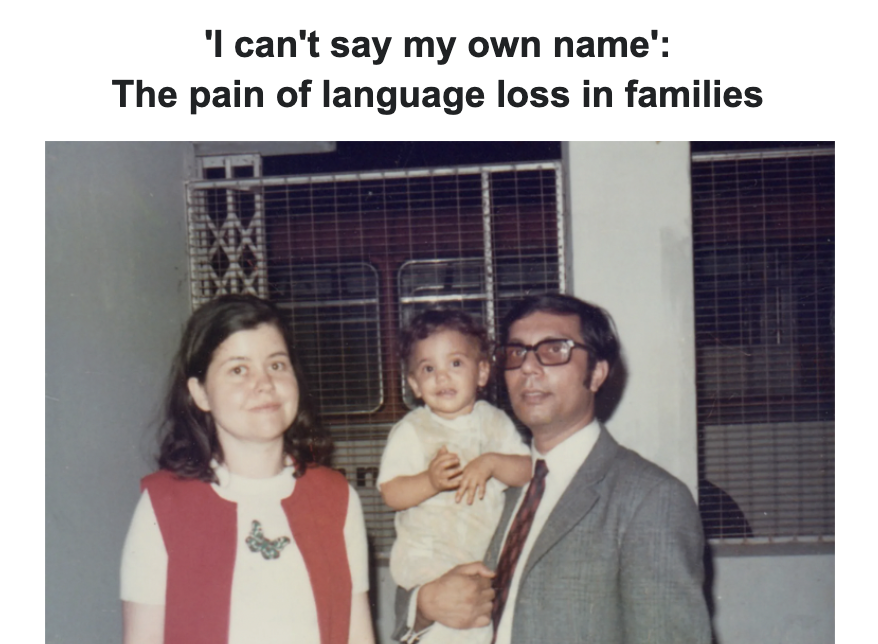

The narrative voice is carefully structured to evolve. The article begins with anecdotal confession, transitions into research-supported analysis, and ends with reflective social commentary. This shift in register, from personal to academic and back to reflective, allows Sanyal to combine emotional authenticity with intellectual credibility. The article also employs circular framing. It begins with her inability to pronounce her own name and later returns to the importance of teachers pronouncing children’s names correctly. This structural symmetry links private pain to public responsibility. The personal detail becomes emblematic of a larger social issue. Layout and visuals further reinforce this structure. Short paragraphs emphasise key emotional statements, giving them visual weight. The inclusion of a childhood photograph of Sanyal with her parents strengthens the autobiographical voice and visually underscores the generational dimension of language loss. The image makes the narrative tangible, reinforcing the human cost behind the statistics.

Through deliberate choices in perspective, tone, reader engagement, emotional reflection, and structural development, Sanyal constructs a narrative voice that transforms private shame into shared understanding. By blending autobiographical confession with sociolinguistic research, the article reframes heritage language loss as a common social phenomenon rather than a personal failure. Ultimately, the text succeeds in humanising the issue and inviting readers to reconsider how multilingual identities are valued within families and society.