How to Write a Killer Paper 1 Introduction — for IB LangLit students

You know that sinking feeling: you’ve just read the unseen text, your mind alive with insights, but when you start writing, your opening lines fall flat.

“This text is about gender inequality…” or “The writer uses bold font to show empowerment…”, phrases that sound less like analysis and more like summary.

The issue isn’t your understanding; it’s the habit of reporting what a text says instead of interrogating how it works.

In Paper 1, that distinction is decisive. The highest-scoring responses don’t guess at intent, they analyse how visual and verbal strategies construct meaning, position the audience, and critique ideologies.

Let’s rewrite your introduction so it begins not with observation, but with interpretation: sharp, text-bound, and unmistakably yours.

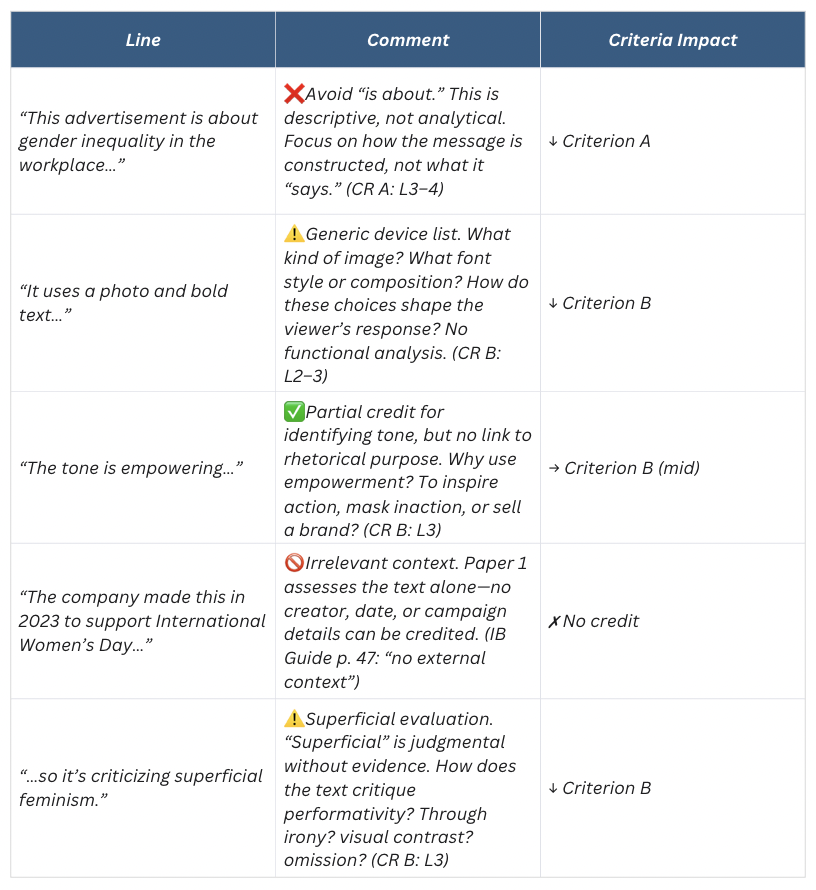

WEAK INTRODUCTION

“This advertisement is about gender inequality in the workplace. It uses a photo of a woman and bold text to show that women deserve equal opportunities. The creators made it to support feminism and raise awareness.”

Examiner Comments

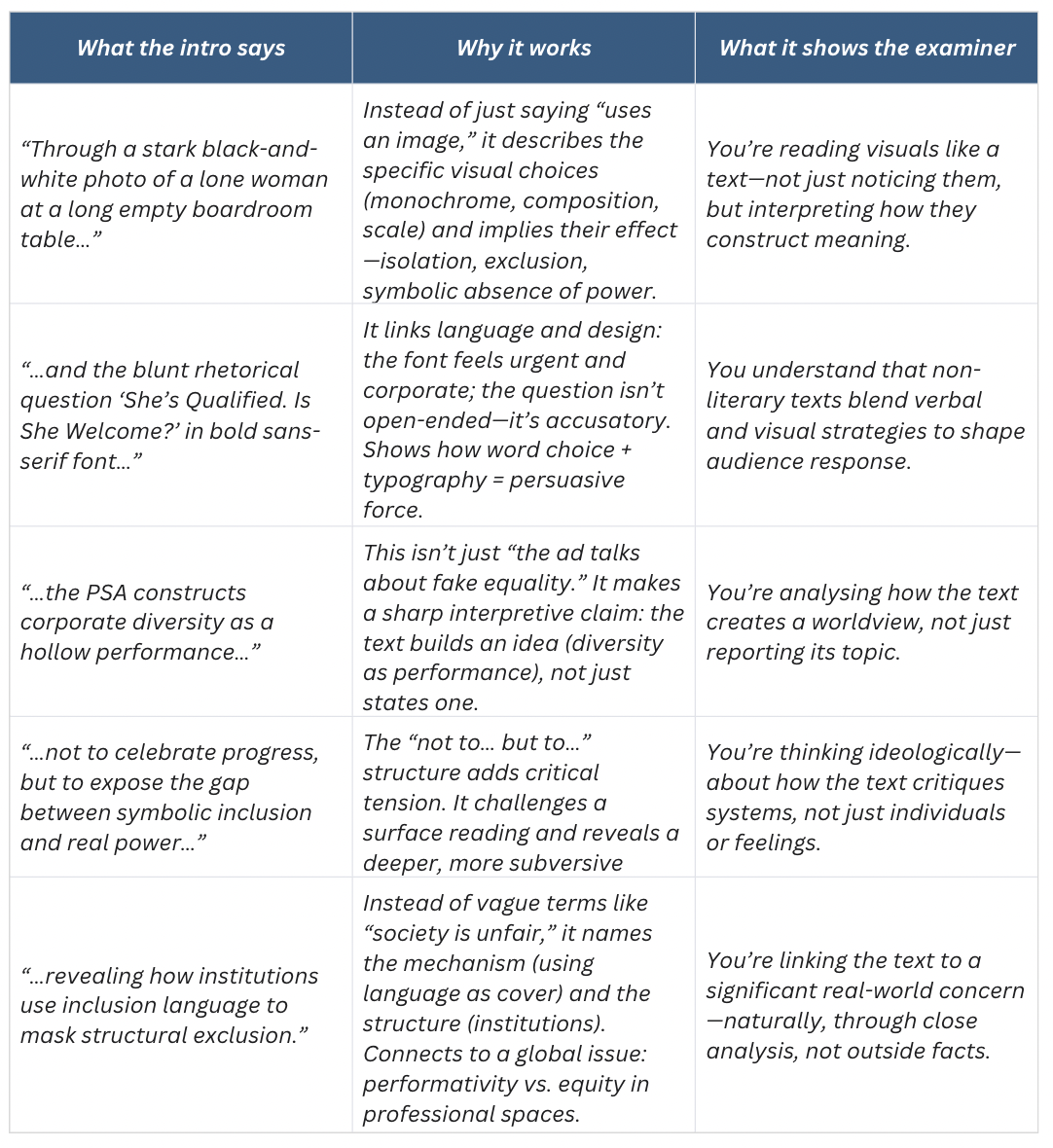

STRONG INTRODUCTION

”Through a stark monochrome image of a solitary woman dwarfed by an empty executive table and the blunt imperative ‘She’s Qualified. Is She Welcome?’, the PSA constructs corporate diversity as a hollow performance, not to affirm progress, but to expose how institutions weaponise inclusion rhetoric while resisting structural change, revealing the gap between symbolic representation and actual power.”

Examiner Comments

Examiner’s Overall Comment

→ “Competent understanding of the topic but limited analysis; relies on summary and assumption.” (Typical feedback: “Move beyond what the text appears to sayanalyse how its visual and verbal strategies construct meaning and position the audience.”)

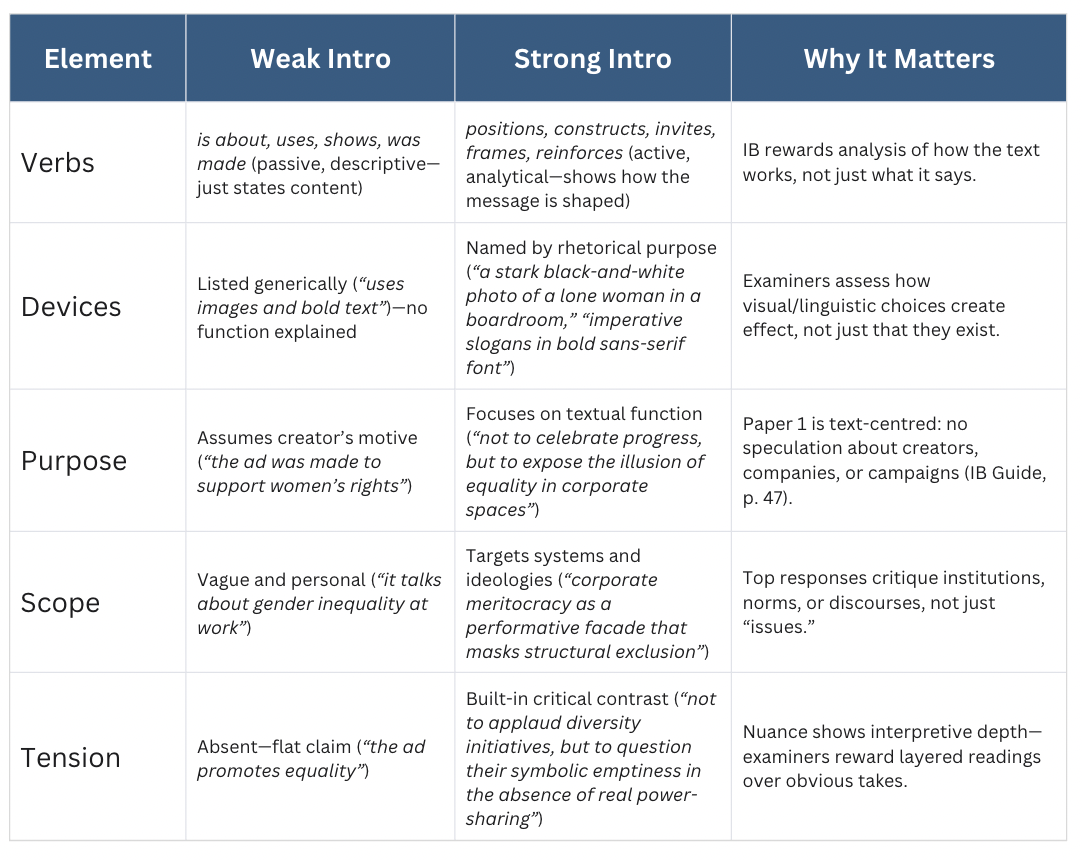

Key Contrasts: What Changed?

The goal of Paper 1 isn’t to uncover a hidden “message” or declare what a text “is about.” It’s to demonstrate how meaning emerges through deliberate choices, how a monochrome palette isolates, how a rhetorical question accuses, and how typography performs urgency.

Examiners aren’t looking for your opinion on feminism or corporate ethics; they’re listening for your ability to trace the mechanics of persuasion, irony, or critique within the text itself.

When you replace “This ad shows inequality” with “Through stark visual contrast and an unanswerable question, the text frames corporate diversity as performative,” you shift from spectator to analyst.

That’s the move: stop telling the examiner what the text says, show them what it does, and how. That’s where top-level analysis begins, not with summary, but with scrutiny.