Organising a Paper 1 Response — November 2025 “The Practical Magic of Painting”

You can access the article is here.

This IB English A Language and Literature Paper 1 analysis explores the opinion article “The Practical Magic of Painting” by Joe Bennet, examining structure, language devices, and visual elements, multimodal elements, and text type. A clear, student-friendly breakdown, along with an essay, designed to help IB learners master textual analysis.

Paper 1 Analysis

Structural devices

Rhetorical opening (“What do I know about painting? Nothing at all.”) → Reassures ordinary readers that expertise isn’t required to appreciate art.

Chronological development (wealth → Reformation → still lifes) → Makes art history accessible and easy to follow for non-specialists.

Problem–solution shift (loss of church patronage → new subjects) → Engages readers by framing history as a story of adaptation and ingenuity.

Return to the lobster image at the end → Reinforces the central idea in a memorable, satisfying way for casual readers.

Language devices

Colloquial tone (“Hell no. I have eyes.”) → Makes the discussion of high art feel informal and inclusive rather than elitist.

Rhetorical questions → Directly involve readers, encouraging them to reflect rather than passively consume information.

Extended listing of objects (lobster, oyster shells, bread, birds, wine glass) → Creates vivid imagery that helps readers visualise the paintings without needing specialist knowledge.

Sensory imagery (“nacreous”, “bulbous flank”, “eye clouding over”) → Appeals to readers’ senses, making the art feel immediate and tangible.

Metaphor (“magic”, “floating down time’s river”) → Elevates the subject in a poetic way that inspires awe in a broad audience.

Contrast (ephemeral life vs enduring art) → Encourages readers to reflect on mortality and permanence, giving the article emotional depth.

Hyperbole (“still the best painting ever”) → Conveys enthusiasm, making the writer’s passion infectious.

Religious allusion (“resurrection and the life”) → Resonates culturally with readers familiar with Christian references, elevating ordinary objects.

Visual imagery devices

Detailed descriptions of texture and light → Help readers mentally “see” the paintings, compensating for those who may not be familiar with them.

Focus on everyday objects → Makes art relatable to readers by connecting it to ordinary domestic life.

Multimodal elements (newspaper context)

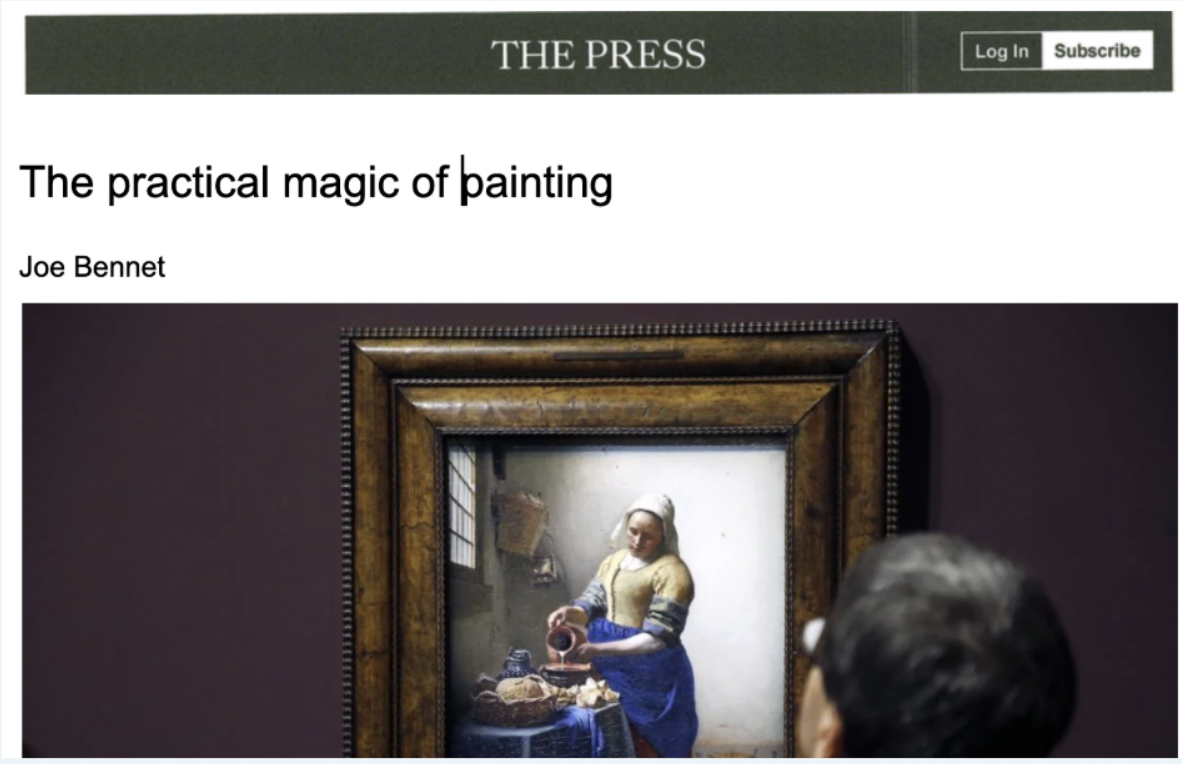

Image of Vermeer’s The Milkmaid → Provides a visual anchor that supports readers’ understanding and appreciation.

Caption highlighting its age (“nearly 400 years on…”) → Reinforces the idea of art’s timeless appeal.

Opinion format

Signals to readers that this is a personal reflection, encouraging engagement rather than academic distance.

Essay

This text is an opinion newspaper article about 17th‑century Dutch still life painting, commenting on the enduring power and accessibility of art. It is targeted at a general newspaper readership, specifically those who may feel intimidated by “high art” or believe that expertise is required to appreciate it. The purpose is to celebrate the technical mastery of Dutch painters while persuading readers that art appreciation is instinctive and democratic. This aim is accomplished through a personal-to-philosophical conceptual progression, a conversational opinion-column layout, colloquial and rhetorical language, sensuous descriptive imagery of everyday objects, and the reinforcing relationship between the reproduced image of The Milkmaid and the article’s argument about art’s timelessness.

Bennett organises the article in a way that gradually builds his argument. He begins with a personal rhetorical opening, “What do I know about painting? Nothing at all”, before expanding into historical context and finally arriving at a philosophical meditation on art and time. This progression from personal anecdote to broader reflection mirrors the reader’s own potential journey from uncertainty to appreciation. The historical explanation of 17th‑century Dutch wealth and the impact of the Reformation functions as a cause‑and‑effect narrative. The loss of church patronage becomes the catalyst for innovation, as painters turn to everyday subjects. This problem–solution dynamic presents artists as adaptable craftsmen rather than romantic geniuses, aligning with Bennett’s larger argument that greatness lies in skill. The essay concludes by returning to the lobster image, creating structural cohesion and reinforcing the central idea that painting preserves what would otherwise decay. This circularity strengthens the persuasive impact for a general audience.

As a newspaper opinion piece, the article is clearly segmented with a headline, byline, date, and short paragraphs. The headline, “The practical magic of painting,” immediately juxtaposes practicality with wonder, encapsulating the argument before the reader begins. The brevity of paragraphs and the conversational flow make the text visually accessible and unintimidating, appealing to busy newspaper readers. The inclusion of a large image of Vermeer’s The Milkmaid, accompanied by a caption referencing its age (“nearly 400 years on”), reinforces the article’s focus on timelessness. The layout therefore supports the argument by positioning painting as both historically distant and immediately visible.

Bennett’s language is deliberately informal and conversational. The blunt phrase “Hell no” disrupts expectations of high-art discourse and reassures readers that expertise is unnecessary. Rhetorical questions engage readers directly, transforming the article into a dialogue rather than a lecture. Extended listing, “a lobster… oyster shells… a torn loaf… dead birds… hydrangeas… a fish… a wine glass”, creates abundance and sensory richness. This accumulation mirrors the density of Dutch still life compositions while immersing readers in vivid detail. Adjectives such as “nacreous,” “bulbous,” and “clouding over” foreground texture and decay, emphasising mortality. Metaphor is central to the article’s persuasive effect. Bennett describes painting as “magic” and imagines the lobster “floating down time’s river for century on century.” This extended metaphor elevates painting from craft to transcendence. The biblical allusion “the resurrection and the life” further sanctifies the preserved lobster, ironically elevating the ordinary. These devices encourage readers to view still life as profound rather than mundane.

Although the article is textual, Bennett’s descriptive language recreates visual experience. His focus on light, objects “reflecting” or “letting it pass through”, mirrors the technical preoccupation of Dutch painters. The tactile detail of “a bead of water on a nasturtium leaf” or “the shimmer of a pigeon’s breast” allows readers to mentally visualise surfaces and textures. By concentrating on everyday domestic objects, Bennett makes art relatable. Readers recognise bread, fish, and wine glasses from their own lives, reinforcing his argument that painting is rooted in the ordinary. The detailed imagery effectively demonstrates the very skill he praises.

The interaction between text and the accompanying image of The Milkmaid strengthens the article’s message. While Bennett discusses painting’s ability to capture fleeting moments, the reproduced artwork visually proves this claim. The caption emphasising that the painting still “beguiles” nearly 400 years later directly supports Bennett’s theme of timelessness. Furthermore, the opinion format signals personal reflection rather than academic authority, aligning with Bennett’s democratic message. The visual presence of the artwork alongside his conversational prose reinforces the accessibility of art appreciation for a modern newspaper audience.

Through its carefully structured progression, accessible layout, conversational language, vivid imagery, and integration of visual elements, the article successfully fulfils its purpose. Bennett persuades general readers that painting is neither elitist nor obscure but a practical craft capable of extraordinary preservation. By framing still life as both modest and magical, he invites his audience to recognise that appreciating art requires nothing more than attentive seeing.