Analysing Relationships in Drama: Shanley’s Doubt (IB Literature May 2024 Past Paper 1)

John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt: A Parable,

Writers show relationships in drama by using different techniques to reveal how characters connect, feel, fight, or grow. These techniques help the audience understand the emotions, conflicts, and changes in the characters’ relationships. Below are some of the key ways writers explore relationships in plays, with clear explanations and examples. As you read through these points, remember that there’s an exemplar essay waiting for you at the end to help tie everything together. The extract is here.

How Writers Show Relationships in Drama

In this extract from John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt: A Parable, the complex relationship between Sister Aloysius, the strict and authoritative principal, and Sister James, the inexperienced and idealistic teacher, is explored through techniques such as dialogue, stage directions, and power dynamics. Their interaction highlights themes of authority, mentorship, and the emotional toll of their contrasting approaches to teaching and faith.

1. Dialogue and Subtext

"The Conversation"

by Henri Matisse

This painting conveys tension and unspoken emotions between two figures, much like the subtext in dialogue.

What it does: Sister Aloysius’ dialogue is assertive and filled with subtext, reflecting her authority and critical view of Sister James. While she outwardly offers advice, her words are layered with judgment.

Example: The line, “You like to see yourself ten feet tall in their eyes,” carries an accusation beneath its seemingly instructive tone. Sister Aloysius implies that Sister James is overly focused on being admired rather than being effective, revealing her disapproval. Similarly, Sister James’ hesitant responses, such as “Oh dear. I had no conception!” show her discomfort and insecurity, exposing the power imbalance in their relationship.

How it works: This dialogue reveals the tension between them. Sister Aloysius’ words push Sister James to self-reflect while asserting her dominance, and Sister James’ responses show her struggle to reconcile her idealism with Sister Aloysius’ harsh worldview.

2. Stage Directions

"The Ballet Class"

by Edgar Degas

Captures movement, posture, and positioning, akin to how stage directions guide actors on stage.

What it does: The stage directions highlight the emotional strain in their relationship.

Example: When Sister James “cries a little,” it underscores her vulnerability and emotional fragility in the face of Sister Aloysius’ criticisms. In contrast, Sister Aloysius’ command, “No tears,” reflects her stern and unsympathetic demeanor, emphasizing her role as a disciplinarian.

How it works: The physical actions and reactions of the characters deepen the audience’s understanding of their dynamic. Sister James’ tears show her inner conflict and feelings of inadequacy, while Sister Aloysius’ cold response reinforces her strict, no-nonsense personality.

3. Conflict and Tension

"The Raft of the Medusa"

by Théodore Géricault

A dramatic depiction of struggle and survival, mirroring the intensity of conflict in storytelling.

What it does: The conversation is driven by conflict, as Sister Aloysius challenges Sister James’ teaching methods and character.

Example: Sister Aloysius’ criticism—“You’re showing off. You like to see yourself ten feet tall in their eyes”—creates tension, as Sister James is forced to confront a harsh view of herself. The power struggle is evident in Sister James’ defensive responses and her eventual emotional breakdown.

How it works: The conflict exposes the contrasting philosophies between the two characters. Sister Aloysius believes in discipline and vigilance, while Sister James embodies innocence and compassion. This tension reflects larger themes of the play, such as the struggle between tradition and progress.

4. Symbolism and Motifs

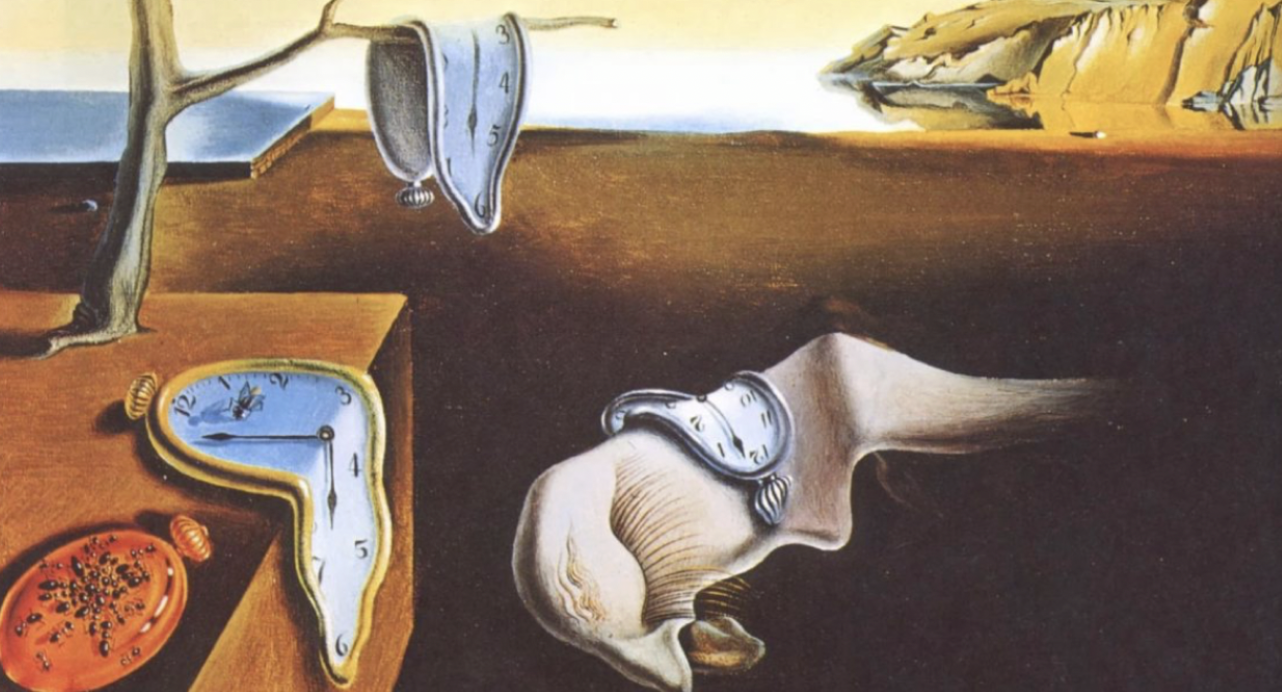

"The Persistence of Memory"

by Salvador Dalí

Laden with recurring symbolic elements like melting clocks, representing themes of time and decay.

What it does: Shanley uses symbolic language to convey the characters’ differing views on teaching and human nature.

Example: Sister Aloysius’ statement, “Boys are made of gravel, soot, and tar paper,” symbolizes her cynical outlook on humanity, particularly young boys. This contrasts with Sister James’ more optimistic view, as she insists, “I feel I know how to handle them.”

How it works: The metaphor of boys being rough and unrefined reflects Sister Aloysius’ hardened perspective on life and her belief in strict discipline. This symbolism deepens the audience’s understanding of their clashing worldviews.

5. Character Growth or Stagnation

What it does: The extract hints at potential growth for Sister James, as she begins to question herself and her methods.

Example: Lines such as, “Do I perform?” and “I thought you were satisfied with me,” show Sister James’ self-doubt growing in response to Sister Aloysius’ criticisms. Her emotional reaction suggests that she is beginning to shed her innocence and naivety, as Sister Aloysius demands.

How it works: Shanley shows how relationships can act as catalysts for personal change. Sister James’ vulnerability contrasts with Sister Aloysius’ unyielding nature, emphasizing how their dynamic forces Sister James to confront the harsh realities of her role.

6. Power Dynamics

"Napoleon Crossing the Alps"

by Jacques-Louis David

A striking representation of authority, control, and dominance in visual form.

What it does: The extract showcases the clear power imbalance between Sister Aloysius and Sister James.

Example: Sister Aloysius asserts her authority through commanding language, such as, “Be hard on the bright ones,” and “No tears.” She controls the conversation, leaving little room for Sister James to voice her perspective.

How it works: The relationship reflects a hierarchical dynamic, with Sister Aloysius positioned as the dominant mentor figure and Sister James as the submissive, uncertain protégé. This imbalance not only defines their relationship but also highlights broader themes of authority and control within the play.

Focus on Six Key Elements

Relationships are the heart of storytelling, revealing hidden emotions, power struggles, and growth. To truly understand these connections, focus on six key elements:

Study Dialogue to uncover hidden emotions and conflicts—what’s said and unsaid often reveals the most.

Notice Actions to observe gestures, tone, and movements that add emotional depth.

Examine Conflict to understand how disagreements or struggles test relationships.

Find Symbolism that reflects the dynamics between characters, often through recurring imagery or objects.

Track Growth to see how relationships evolve, change, or stagnate over time.

And finally, Analyze Power to explore authority, resistance, and how characters assert themselves.

Until next time, keep reading, keep exploring, and keep discovering!When it comes to analyzing relationships in any text, there are six key areas to focus on:

Examplar Essay Response (May 2024)

In the extract from Doubt: A Parable by John Patrick Shanley, the relationship between Sister Aloysius and Sister James is shown to be tense and difficult, reflecting their deeply opposing beliefs about teaching and authority. Through their conversation, it becomes clear that Sister Aloysius sees herself as a figure of control, while Sister James struggles with her self-confidence in the face of constant criticism. This difference creates an emotional and ideological divide between them, which Shanley explores through their interactions.

Sister Aloysius’ words are sharp and cutting, designed to undermine Sister James’ confidence. When she says, “You’re showing off. You like to see yourself ten feet tall in their eyes,” it is clear that she is accusing Sister James of seeking admiration from her students rather than caring for them sincerely. These words paint a vivid picture of Sister James as someone naive and overly eager to please others. Beneath the surface, however, Sister Aloysius is sending a much harsher message: she doesn’t believe Sister James is fit to teach because of her innocence and kindness. The tension in this moment reflects the broader conflict between their values. Sister Aloysius views discipline and control as the foundation of good teaching, while Sister James sees trust and emotional connection as equally important. This clash of worldviews immediately creates a power imbalance, as Sister Aloysius positions herself as the authority figure who must “correct” Sister James’ approach.

The strain between them is also visible in their actions. When Sister James begins to cry, the audience can see how deeply affected she is by Sister Aloysius’ relentless criticism. Instead of offering comfort, Sister Aloysius says, “No tears,” a command that leaves no room for emotion. This cold response highlights the distance between their personalities. Sister James’ tears show her sensitivity and humanity, while Sister Aloysius’ refusal to acknowledge them reinforces her belief that emotions are a weakness. The contrast between the two is striking: one is vulnerable and open, while the other is rigid and detached. This moment also reflects the power dynamic between them. Sister Aloysius is in complete control of the situation, while Sister James is left feeling small and unsupported. The audience is invited to question whether Sister Aloysius’ strictness is necessary or whether it crosses the line into cruelty.

Their clashing values are perhaps most evident in Sister Aloysius’ view of innocence. She criticizes Sister James directly, saying, “I cannot afford an excessively innocent instructor in my eighth-grade class. It’s self-indulgent.” Her words suggest that she equates innocence with weakness, implying that Sister James’ compassion and trust in her students make her a bad teacher. This perspective shows just how rigid Sister Aloysius’ expectations are—she believes that effective teaching requires constant discipline and vigilance. Her choice of words, especially “self-indulgent,” is particularly harsh, as it implies that Sister James is more concerned with her own feelings than with her students’ needs. This moment captures the ideological conflict between the two: Sister Aloysius values control and structure above all else, while Sister James believes in nurturing her students’ growth through kindness and patience. It is a struggle not just over teaching methods but over how much space there is for humanity and emotion in positions of authority.

The divide between them is also reflected in the way Sister Aloysius sees potential and discipline. When she asks, “What good’s a gift if it’s left in the box?” she is making it clear that she believes talent is worthless unless it is properly developed through hard work and discipline. This idea shows her utilitarian approach to teaching, where results and productivity are more important than emotional growth. The “gift” in this statement symbolizes the natural abilities of both students and teachers, while the “box” represents untapped potential. Sister Aloysius’ frustration with this “unopened box” reflects her dissatisfaction with Sister James, whose compassionate teaching style she sees as too soft and ineffective. This metaphor underscores the deep philosophical divide between the two nuns: for Sister Aloysius, structure and control are everything, while for Sister James, trust and emotional support matter just as much.

In this extract, Shanley explores the conflict between authority and compassion through the relationship between Sister Aloysius and Sister James. Their conversations and interactions reveal how their opposing values create tension and imbalance, with Sister Aloysius’ strictness overshadowing Sister James’ kindness. Through their conflict, Shanley raises important questions about the cost of authority and the difficulty of balancing discipline with humanity.