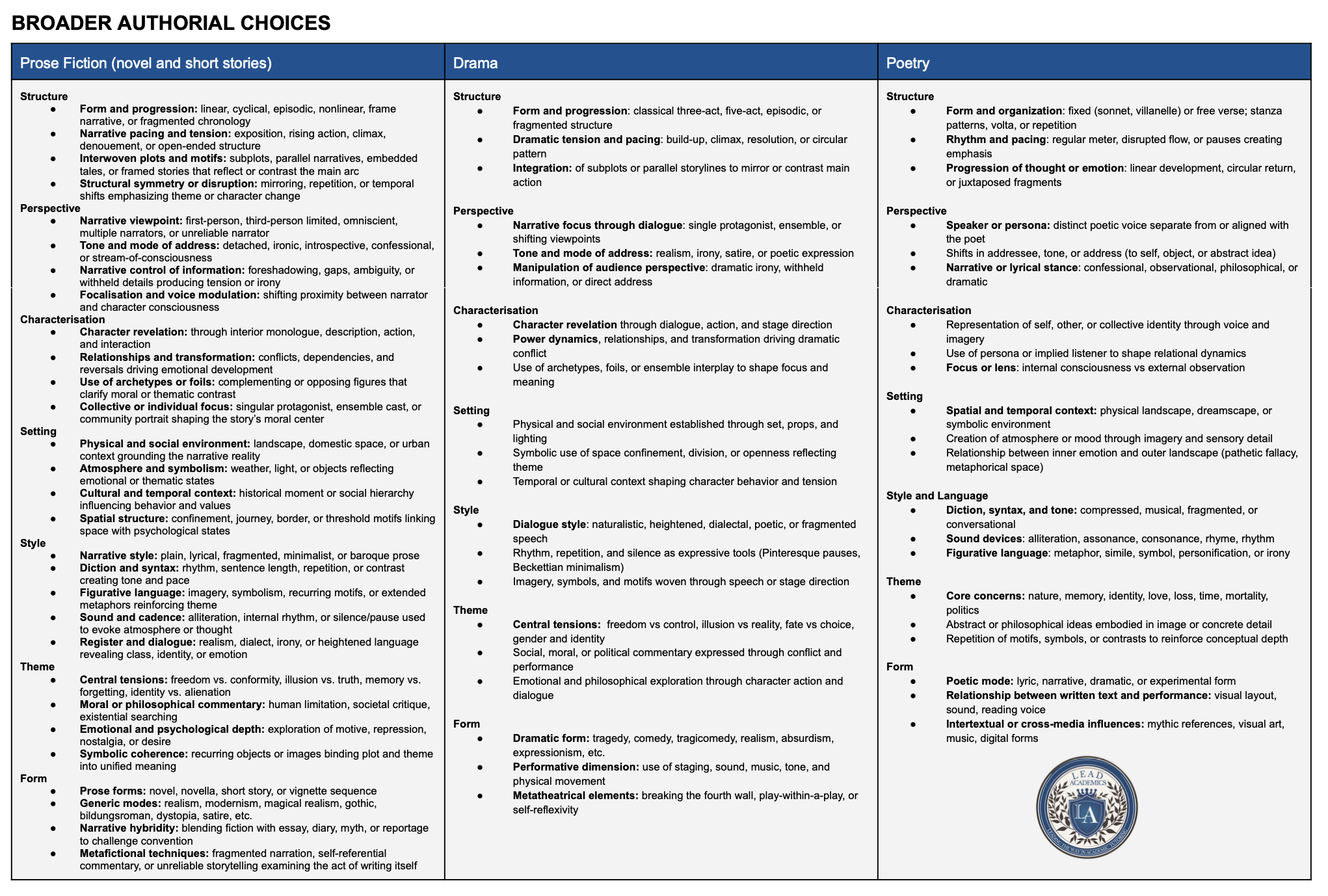

IB English: Paper 2 Organisation

Block Method

In The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald critiques the illusion of the American Dream through Gatsby’s romantic idealism, his pursuit of wealth as social currency, and the ultimate hollowness of material success. His longing for Daisy is crystallised in “the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock,” a symbol of hope that masks an unattainable fantasy. Gatsby reinvents himself, amassing wealth not for its own sake but to reclaim a romanticised past, believing that money can erase class barriers. Yet Nick Carraway’s narration reveals the futility of this quest: Gatsby is “borne back ceaselessly into the past,” trapped in a dream divorced from reality. His tragedy underscores Fitzgerald’s broader critique, that the American Dream has devolved into empty materialism, where image supersedes authenticity.

Similarly, in A Doll’s House, Ibsen dismantles illusions through Nora’s journey, focusing on the performance of domestic bliss, the infantilization of women, and the awakening to selfhood. At first, Nora embraces her role in a seemingly happy marriage, unaware of its constructed nature. Torvald’s patronizing pet names, “little skylark” and “squirrel”, frame her as a charming object, not a thinking equal. Only when her secret loan is exposed does she see the truth: her identity has been shaped by male expectations, not personal agency. Through her declaration, “I have been your doll-wife, just as at home I was Papa’s doll-child,” Ibsen marks the collapse of domestic illusion and the beginning of the human quest for autonomy.

Both texts explore how illusions shape their protagonists’ lives through three parallel points. In The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald shows how Gatsby’s romantic idealism. In A Doll’s House mirrors Nora’s performance of marital happiness. Both characters begin trapped in false emotional worlds. Gatsby’s belief that wealth can function as social currency aligns with Nora’s infantilization under Torvald, since both illusions depend on external roles, status for Gatsby, obedience for Nora, to maintain stability. Finally, the hollowness of material success in Gatsby parallels Nora’s awakening to selfhood, as both characters ultimately confront the emptiness behind the illusions governing their lives. Through these three shared dynamics, each text reveals how seductive fantasies can obscure reality until the moment they collapse.

Alternating Method

Fitzgerald and Ibsen both explore the power and destruction of illusion, but in vastly different social contexts. In The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald presents illusion through Jay Gatsby’s relentless pursuit of Daisy and the American Dream, symbolized by “the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock,” a beacon of hope and unattainable desire. Similarly, in A Doll’s House, Ibsen exposes illusion within marriage as Nora clings to the belief that her seemingly perfect home reflects love and harmony. While Gatsby’s dream reveals the decay of genuine emotion in a world where “he is borne back ceaselessly into the past,” unable to reconcile fantasy with reality, Nora’s illusion unravels as Torvald’s pet names, his “little skylark” and “squirrel”, expose his condescending view of her as decorative rather than equal. Both characters ultimately realise the falseness of their pursuits: Gatsby’s vision of romantic idealism and social mobility collapses with his tragic death, while Nora’s confrontation with patriarchal expectations forces her to admit, “I have been your doll-wife, just as at home I was Papa’s doll-child.” Fitzgerald’s critique of materialism and Ibsen’s critique of gender roles converge to show that the search for meaning within illusion leads not to fulfilment but to an awakening, often painful, but necessary for self-realisation.

Integrated Method

Both Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Ibsen’s A Doll’s House explore how illusion imprisons individuals, yet while Gatsby’s illusions stem from social aspiration, Nora’s arise from domestic expectation. Gatsby’s belief in “the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock” represents a dream of wealth and romantic fulfilment, just as Nora’s faith in her husband’s love represents her dream of security and acceptance. However, Gatsby’s illusion reflects the corruption of the American Dream by materialism, whereas Nora’s reveals how patriarchal society distorts female identity. Nick notes that Gatsby is “borne back ceaselessly into the past,” emphasising how his obsession with reclaiming what is lost mirrors Nora’s struggle to maintain a façade of marital bliss that no longer exists. While Fitzgerald presents love as consumed by money and status, Ibsen reveals love as limited by control and gendered power. Torvald’s condescending pet names, calling Nora his “little skylark” and “squirrel”, parallel Daisy’s objectification by Gatsby, as both women become symbols rather than autonomous individuals. Yet, when their illusions collapse, Gatsby clings to his dream until death, while Nora rejects hers through self-liberation, declaring, “I have been your doll-wife, just as at home I was Papa’s doll-child.” Ultimately, both characters expose the dangers of living within illusion, Gatsby trapped by society’s obsession with wealth and Nora constrained by its moral codes, but whereas Gatsby’s dream ends in ruin, Nora’s disillusionment opens the possibility of freedom.