What Does a Level 7 IB English Paper 1 Actually Look Like? (Nov 2025 past paper)

View the opinion piece here.

Breaking Down a Full‑Marks Paper 1 Response

One of the most common questions IB English students ask is deceptively simple: What does a top‑scoring Paper 1 response actually look like? Mark schemes describe criteria in broad terms, but they rarely show how those criteria come together in a real piece of writing under exam conditions.

This post breaks down a Level 7 (20/20) IB English A: Language and Literature Paper 1 response based on Joe Bennett’s opinion piece, “The practical magic of painting.” Rather than presenting the essay as an untouchable “perfect model,” the aim here is to make the thinking behind it visible, so you can see how examiners reward effective analysis.

Start with Meaning, Not Techniques

A key strength of high‑level Paper 1 responses is that they begin with a clear understanding of the writer’s ideas, not a hunt for techniques. In this example, the student identifies Bennett’s admiration for Dutch still‑life painting and his challenge to modern assumptions about what makes art meaningful. Every analytical point grows out of that understanding, ensuring the response remains focused and relevant.

Analysis That Explains How Language Works

Level 7 responses do more than name literary devices. They explain how language choices shape meaning and reader response. This essay explores Bennett’s use of cumulative listing, juxtaposition, paradox, and sentence structure, consistently linking each feature to its effect. The result is analysis that feels purposeful rather than mechanical.

Building a Clear Line of Argument

Another hallmark of strong Paper 1 writing is organisation. The introduction establishes a clear focus early, and each paragraph develops a single idea that connects back to the central argument. Transitions guide the reader smoothly, showing examiners that the student is in control of their response.

Using Language to Strengthen Analysis

Finally, top‑band answers use precise, confident academic language without sounding inflated. Terminology is accurate, quotations are well integrated, and the tone remains analytical and engaged. This clarity allows the ideas to take centre stage, exactly what examiners want to see.

Why Studying Level 7 Responses Matters

Seeing a full‑marks response alongside examiner‑style commentary helps demystify the assessment criteria. It shows that a Level 7 is not about sounding clever or writing as much as possible, but about reading carefully, thinking clearly, and explaining effects convincingly.

If you’re aiming to improve your Paper 1 performance, use this example as a guide, not something to memorise, but a model for how strong understanding, focused analysis, and clear writing come together to earn top marks.

Exemplar Level 7 IB English Paper 1 (HL)

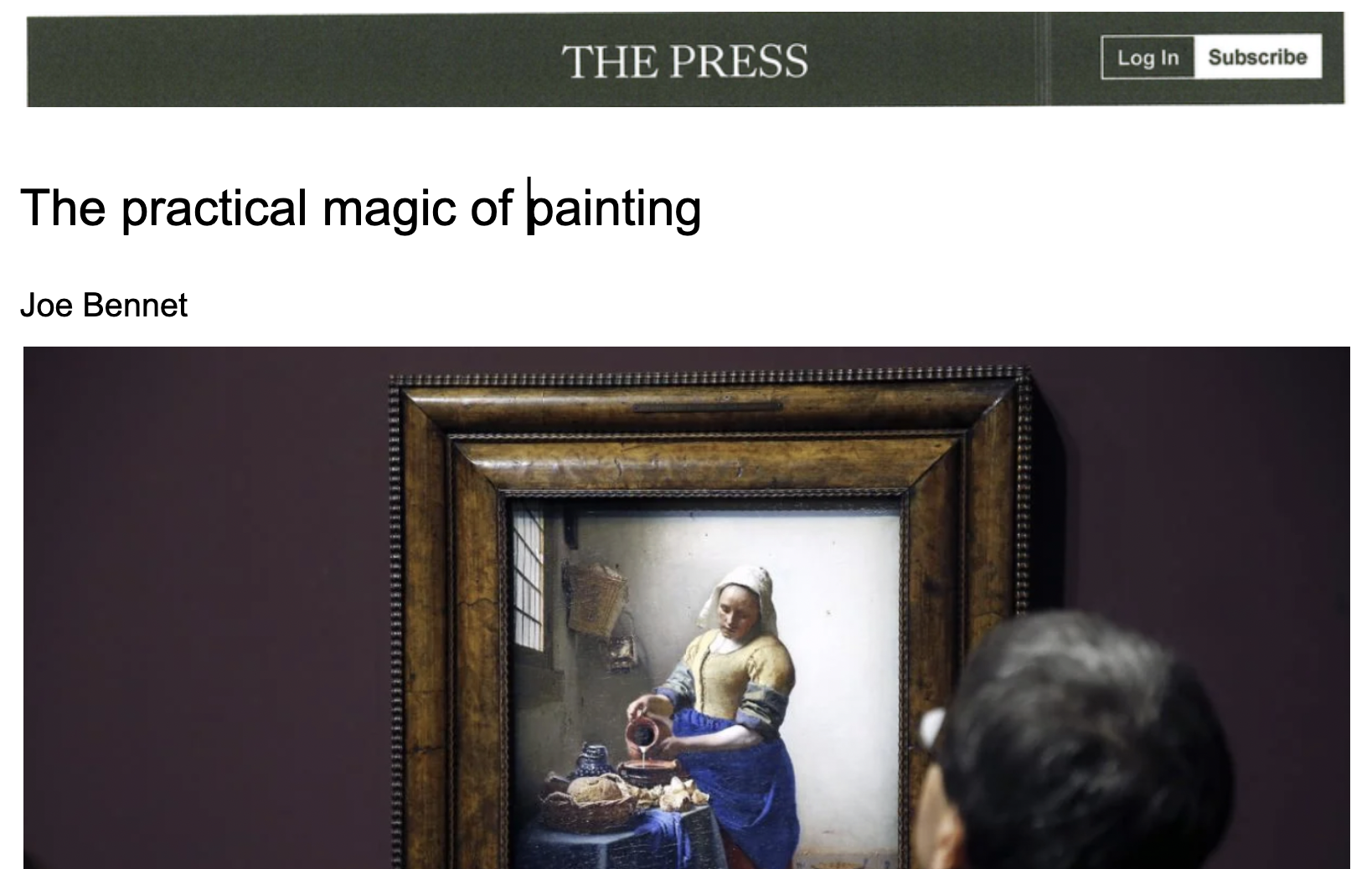

In his opinion piece “The practical magic of painting,” Joe Bennett writes for a general audience, likely everyday readers of The Press who enjoy thoughtful writing but aren’t art experts. His tone is conversational, lightly humorous, and respectful, never condescending or overly academic. Through careful use of language, he expresses deep admiration for 17th-century Dutch still-life painting while quietly challenging modern ideas about what makes art valuable. Rather than using specialist terms or abstract theories, Bennett builds his case with sensory imagery, irony, paradox, and metaphor, all of which help present skilled craftsmanship as something meaningful, perhaps even quietly spiritual.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the way Bennett pulls the reader into the world of Dutch still life with a fast, vivid list: “Take a lobster. Or some oyster shells… Or a torn loaf… Or a heap of dead birds… Or a bunch of hydrangeas… Or a fish, the eye clouding over in death.” The repeated “Or… .” By listing images quickly, one after another, Bennett builds a cumulative effect that mirrors how a still‑life painting brings many objects together in a single frame, drawing the reader into the scene, as if they are standing in front of the painting themselves. He also uses juxtaposition, placing beautiful things like hydrangeas next to signs of decay like dead birds and a fish with a “clouding” eye. This contrast reminds us that life fades and that powerful art doesn’t have to be perfect or pretty. Then he asks a rhetorical question: “Capture any or all of that… and what have you got?” and immediately answers: “You’ve got a Dutch still life… And still the best painting ever.” Moving from an open question to such a strong statement makes his personal view feel obvious and convincing. Through this mix of concrete words, sensory details, and straightforward sentences, Bennett helps us experience the paintings. In doing so, he pushes back against the assumption that art appreciation depends on expert knowledge or formal education.

This democratic view is built right into his voice. Bennet’s tone is shaped by word choice and sentence style that feel familiar, not distant. His opening line, “What do I know about painting? Nothing at all. Does that matter? Hell no. I have eyes”, uses colloquial diction (“Hell no”) and short, punchy sentences to sound confident and relatable. He positions himself as an ordinary observer, not an authority, which makes his opinion feel honest and inclusive. He also uses dry irony and understatement to make subtle critiques, as when he writes, “Calvinism makes no more sense than any other of the thousand versions of religion, but it is more austere.” The wry tone and the contrast between the absurd and the strict gently poke fun at rigid religious rules. At the same time, he shows how those very rules, by banning fancy church art, ended up giving painters the chance to focus on everyday things like bread, birds, or flowers. This quietly challenges the idea that great art has to be about big, serious topics like religion or morality; for Bennett, ordinary life is just as worthy of attention.

He captures this belief most memorably through paradox. The closing line, “They had nothing to say, and no one has said it better”, captures his central idea that great art can communicate deeply without stating a message. He also uses oxymoron in the phrase “practical magic,” combining the ordinary with the extraordinary to describe how painting transforms everyday things into something lasting. This idea returns when he calls a painted lobster “the resurrection and the life,” a biblical allusion applied to something as humble as seafood. The contrast between sacred language and a decaying object highlights his belief that art gives dignity to the ordinary, not by preaching, but by paying close attention. Here, Bennett directly opposes the modern assumption that art must express the artist’s personal views or emotions to be meaningful.

This same belief, that meaning comes from what is shown, not what is said, shapes even the way he writes. Short, blunt sentences like “Money first serves needs” or “Selling was the test and the purpose” reflect the no-nonsense reality of painters who had to earn a living. In contrast, he uses sentence fragments and ellipses: “Everything is ephemeral… But art seems to. It takes the fleeting moment… and holds it still…”, where the pauses mimic the way a still-life painting freezes time, so the form of the writing echoes its subject. Through this contrast, he questions the assumption that true art exists only in protected, institutional spaces; instead, he shows how art born from necessity and daily life can be just as profound.

Through careful use of language, Bennett allows readers to experience firsthand the quiet power of Dutch still lifes by modeling the very qualities he admires in the art itself.

Examiner Commentary and Criterion Breakdown

Criterion A: Understanding and interpretation [Mark: 5/5]

The response shows perceptive understanding of both the literal and implied meanings of the text.

The student correctly interprets Bennett’s admiration for Dutch still life, his challenge to modern assumptions about art, and his democratic positioning of the viewer.

Interpretations go beyond paraphrase, addressing implications (e.g. art not needing expert knowledge, meaning without explicit message).

References are frequent, precise, and integrated, including:

The opening rhetorical questions (“What do I know about painting?”)

The still-life list (“Take a lobster… Or…”)

The paradoxical ending (“They had nothing to say…”)

Biblical allusion (“the resurrection and the life”)

These references are not decorative; they directly support interpretation.

✅ This fits the descriptor: “perceptive knowledge and understanding… effectively supported by convincing references.”

Criterion B: Analysis and evaluation [Mark: 5/5]

The response consistently analyses how stylistic and structural choices shape meaning, not just what they are.

Techniques are:

Identified accurately (cumulative listing, juxtaposition, paradox, oxymoron, irony, rhetorical questions, sentence length, ellipses)

Explained clearly

Evaluated in terms of effect (e.g. how listing mimics still-life composition; how sentence fragments mirror frozen time)

There is strong evaluative language:

“pushes back against the assumption…”

“quietly challenges…”

“the form of the writing echoes its subject”

The analysis is conceptually coherent, returning repeatedly to the central idea of meaning without proclamation.

✅ This is insightful analysis and evaluation, not feature-spotting.

Criterion C: Coherence, focus and organisation [Mark: 5/5]

The introduction clearly establishes:

Text type

Audience

Tone

Central interpretive focus

Each paragraph:

Develops one clear idea

Uses textual evidence strategically

Links back to the central argument

Transitions are logical and smooth (“This democratic view…”, “He captures this belief…”, “This same belief…”).

The line of argument is sustained and controlled throughout, with no digressions or repetition.

✅ The response demonstrates effective coherence, focus, and organisation.

Criterion D: Language [Mark: 5/5]

Vocabulary is precise, varied, and academic, without being inflated.

Terminology is used accurately:

“cumulative structure”

“juxtaposition”

“paradox”

“oxymoron”

“biblical allusion”

Sentence control is excellent, with fluent integration of quotations.

Tone is appropriate for literary analysis: confident, clear, and analytical.

No noticeable errors that interfere with meaning.

✅ Language is convincingly accurate, varied, and effective.

Key Takeaways for IB Paper 1 Success

In short, a successful IB Paper 1 response is not about sounding impressive or identifying as many techniques as possible; it is about showing how language creates meaning. As this Level 7 example demonstrates, strong analysis grows from a clear focus, well-chosen textual evidence, and consistent explanation of effects. By staying anchored in the guiding question and responding thoughtfully to the writer’s choices, you too can move beyond description and into interpretation, exactly what IB examiners are looking for.