Essay on Analysing a Diary Entry — Samuel Pepys’ The Great Fire of London (Nov 2014 IB past paper)

Watch the vlog here.

Samuel Pepys’ tone in documenting the Great Fire of London, in his diary on Sunday, 2 September 1666, transitions from detachment to deep emotional engagement as the catastrophic event unfolds. Initially, Pepys is calm and unconcerned, dismissing the fire as distant and minor. However, as the fire spreads rapidly, his tone becomes worried and troubled, revealing his growing anxiety. As he witnesses the chaos and destruction firsthand, Pepys adopts an alarmed and observant tone, carefully documenting the frantic efforts of the people and the fire’s devastating effects. Finally, by the end of the entry, his tone is horrified and reflective, as he contemplates the scale and ferocity of the disaster. This progression in tone highlights Pepys’ increasing emotional engagement, from a passive observer to an empathetic chronicler of London’s catastrophic events.

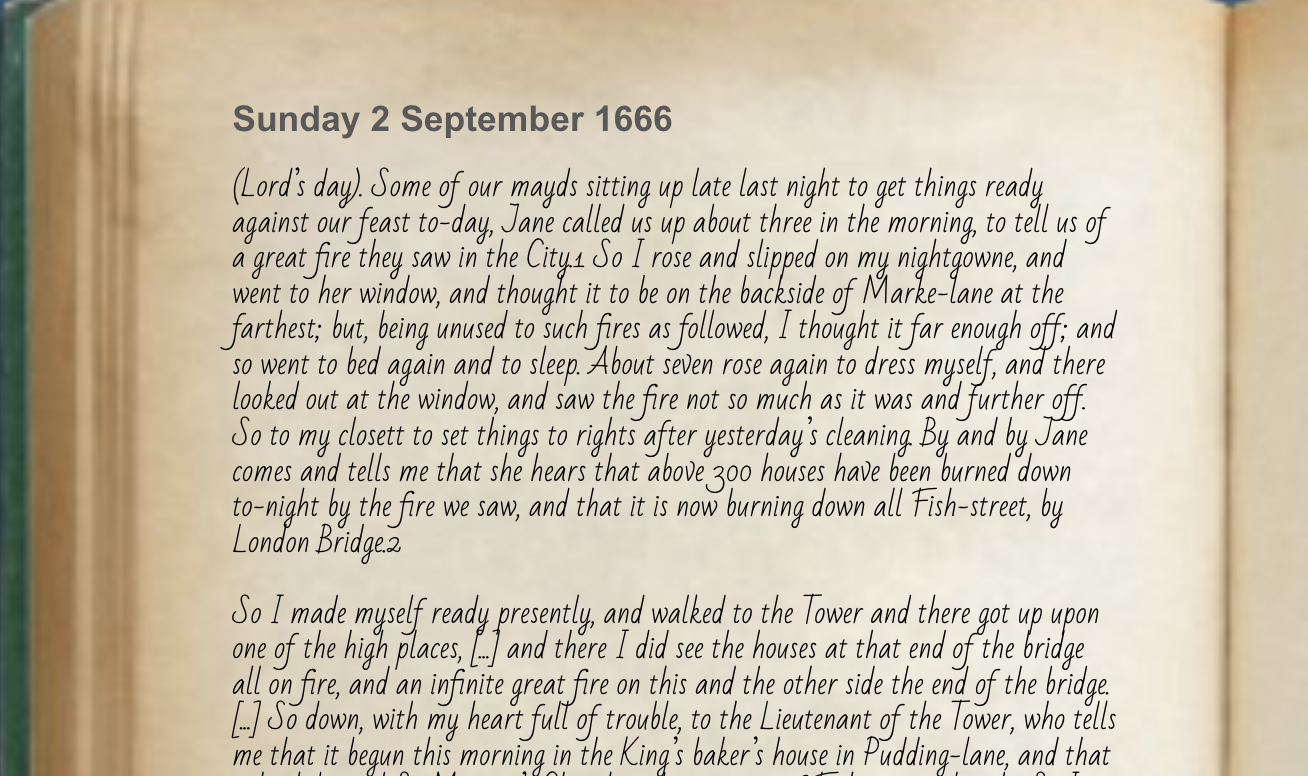

At the beginning of the diary entry, Samuel Pepys exhibits a calm and unconcerned tone, reflecting his initial detachment from the fire. Upon being awakened by his maid, Jane, to inform him about a fire in the city, Pepys casually observes it from his window. He writes, “I thought it to be on the backside of Marke-lane at the farthest; but, being unused to such fires as followed, I thought it far enough off; and so went to bed again and to sleep.” The use of spatial imagery in “on the backside of Marke-lane at the farthest” emphasizes the physical distance Pepys perceives between himself and the fire, reinforcing his sense of safety. Additionally, the repetition of "thought" highlights his assumption-driven complacency, showing his lack of urgency. His decision to return to bed and sleep further underscores this sense of detachment and is an example of understatement, as his casual dismissal belies the looming disaster. At this stage, Pepys’ calm tone and passive actions characterize him as a detached observer, oblivious to the scale of the unfolding events.

However, as the fire begins to spread with alarming speed, Pepys’ tone shifts to one of worry and growing anxiety. After being awakened a second time and realizing the fire’s severity, he writes, “So down, with my heart full of trouble, to the Lieutenant of the Tower, who tells me that it begun this morning in the King’s baker’s house in Pudding-lane, and that it hath burned St. Magnus’s Church and most part of Fish-street already.” The metaphor “heart full of trouble” vividly conveys the emotional weight Pepys experiences as he begins to grasp the scale of the fire’s destruction. Additionally, the specificity of detail in the Lieutenant’s account—naming the origin of the fire in “the King’s baker’s house in Pudding-lane” and listing the landmarks already consumed—serves as a form of foreshadowing, hinting at the vast devastation yet to come. The juxtaposition between Pepys’ earlier calm and his current worry highlights the rapid escalation of the disaster and its emotional impact on him. At this point, Pepys transitions from a detached observer to someone deeply troubled by the scope of the unfolding catastrophe.

As he witnesses the chaos and destruction firsthand, Pepys adopts an alarmed and observant tone, carefully documenting the frantic efforts of the people and the fire’s devastating effects. When Pepys ventures out to observe the fire firsthand, his tone becomes alarmed, yet he maintains a keen sense of observation. He provides vivid descriptions of the chaos and destruction caused by the fire, focusing on the frantic actions of the citizens: “Poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then running into boats, or clambering from one pair of stairs by the waterside to another.” The visual imagery in this passage vividly depicts the desperation and urgency of the people, allowing readers to imagine the horrifying scene of individuals fleeing for their lives. The repetition of active verbs—“staying,” “running,” “clambering”—conveys the frantic and uncoordinated movements of the populace, emphasizing their panic. Additionally, Pepys employs contrast between the people’s initial reluctance to leave their homes and their eventual desperate flight, illustrating their struggle to accept the reality of the fire’s immediate danger. Despite his alarm, Pepys takes care to document the scene in detail, demonstrating his role as a chronicler. His use of precise observational language ensures that the physical devastation and emotional toll of the disaster are preserved for posterity. Through opposing tones, alarming yet observant, Pepys conveys both the chaos of the moment and his commitment to capturing it accurately.

By the end of the entry, his tone is horrified and reflective, as he contemplates the scale and ferocity of the disaster. As night falls and the fire continues to rage, Pepys’ tone becomes horrified and reflective. He describes the fire with vivid and emotional language, emphasizing its terrifying and destructive power: “As it grew darker, [the fire] appeared more and more, and in corners and upon steeples, and between churches and houses, as far as we could see up the hill of the City, in a most horrid malicious bloody flame, not like the fine flame of an ordinary fire.” The adjectives “horrid,” “malicious,” and “bloody” evoke a sense of malevolence, personifying the fire as a destructive force with almost intentional cruelty. The juxtaposition between “the fine flame of an ordinary fire” and the “bloody flame” of the Great Fire underscores the unparalleled ferocity of this disaster, emphasizing its extraordinary and terrifying scale. Additionally, the alliteration in “horrid, malicious bloody flame” creates a rhythmic emphasis that mirrors the relentless and consuming nature of the fire. Pepys’ use of spatial imagery—noting the fire’s spread “in corners and upon steeples, and between churches and houses”—paints a vivid picture of the fire’s omnipresence, suggesting that no part of the city is safe. This tonal progression reveals the writer's desire to move beyond surface-level reactions and encourage a more profound understanding of the human cost and emotional weight of the disaster.

Through these tonal shifts, Samuel Pepys’ diary entry captures the emotional trajectory of someone witnessing one of the most catastrophic events in London’s history. His progression from calm detachment to horrified reflection mirrors the escalating intensity of the Great Fire, transforming his role from a passive observer to an empathetic chronicler of the disaster. These tonal changes provide readers with a vivid and human perspective on the unfolding tragedy.